exhibitions online

—what for?

Notes from the 2020 Curatorial Workshop | 23-26 June 2020 |Bucharest Biennale.

During COVID19 crisis many arts institutions have transferred existing programme, or created new programme online. This has given rise to a vast digital publishing drive.

The impulse to push content online is widespread and may seem unremarkable in some ways, seen simply as a means to provide access to artistic work and ideas, while many people experience “downtime”, constrained to stay at home and often to stay “on screen.”

However, it is notable that there are also some attempts, to propose a relationship between the terms of the COVID19 crisis, societal disruption and current political protest. Thus L’Internationale confederation of museums, through the “Our Many Europes” project (of which HDK-Valand, University of Gothenburg is an associate academic partner,) have launched an ‘artists in quarantine’ programme commissioning artists (with payment) to produce work online, drawing upon the way balconies appear to provide newly important public spaces, while traditional street spaces have been evacuated or barred from access.

L’Internationale’s project invited artists Babi Badalov, Osman Bozkurt, Simnikiwe Buhlungu, Ola Hassanain, Sanja Iveković, Siniša Labrović, Rogelio López Cuenca & Elo Vega, Kate Newby, Daniela Ortiz, Zeyno Pekünlü, Maja Smrekar, Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, Guy Woueté, Akram Zaatari, and Paweł Żukowski to: “join a conversation from their present working and living spaces, conditions and places.”

Ideas proposed included “new perspectives on public/private space, solidarity” and acts of “critique that are intrinsically connected with the present time.” Speaking of a “time of global isolation, virtual space, as well as the windows, balconies or facades of our homes have taken on the role and importance of town squares for collective expression, while also blurring the boundaries between public and private spheres.” Artists in Quarantine “is a modest way to contribute to the conversation about the effects of the current pandemic, redeliberating the communication channels that have influenced the present perception and consumption of information, as well as rethinking the potentiality of existing spaces.”

“Artists’ contributions will be shared online through L’Internationale’s social media channels, @internationaleonline, and via the websites and social media channels of members of the confederation from April 21st. Artists’ proposals will be published twice a week, every Tuesday and Thursday.”

The German art theorist and critic Jörg Heiser responded with a well defined critique “‘Artists in Quarantine,'” public intellectuals, and the trouble with empty heroics” that pointedly warned against the project’s rhetorical framing as over-reaching and “confused”: “To subvert power you need a clear idea of what it is you’re attempting to resist. Without that, the invocation of resistance in the name of civil rights or progressive goals is ineffective, counterproductive, or simply false. This confusion lies at the heart of a project that runs the risk of conflating temporary measures to protect the vulnerable with the historic example of Iveković’s stance against state repression.”

Heiser moves from the online art commissions, without missing a beat, to the critical reading of contemporary “protest” as also at risk of similar confusion that “might underpin the assessment of protests in general: Are they resisting a government whose dictatorial tendencies are supposedly manifested in the implementation of lockdown measures? Or are they resisting a government whose dictatorial tendencies are manifested in their reckless disavowal of such lockdown measures?” The stakes are high here in Heiser’s reading of these protests:

“In its most extreme form, the talk about ‘herd immunity’ and the agitation against lockdowns has turned into a eugenic-neoliberal death cult exemplified by the lieutenant governor of Texas, Dan Patrick, who stated in an interview with Tucker Carlson on Fox News on April 20 that ‘there are more important things than living.'”

This discussion moves—by analogy, “a similar confusion”—from the case of a museum’s rhetoric in commissioning artists to generate content, for distribution via social media channels, responding to their COVID19 contexts, to a larger diagnosis of what is at stake in the current political cultural conjunction of capital, mass death and population management (biopolitics/necropolitics). That move may seem inflationary in some way: going from a self-declared ‘modest’ instagram art project to a summary account of the terms and stakes of the current historical moment.

However, it is worth considering how different museums, in their transfer to online channels as their primary public facing mode of utterance, are also opening up a similar scale-shift – from an on-line temporary distribution of art works and related materials, to specifying the stakes of, or claiming positions within, the current historical moment. MOMA again (notoriously a ‘white’, ‘white cube’) is a useful example here.

let’s go online…

In a recent e-flux Journal editorial Tom Holert, Doreen Mende and the editorial team start by describing the whole transfer of ‘life’ to the online screen: “Today, living through the planetary pandemic, the imperative to navigate the world and our own lives through computational tools has been radicalized to the extreme. The last months of Skyping, Zoom conferencing, and collaborative Google Docs writing make us feel we have no choice but to exhaust the planetary promise of navigational tools, refining remoteness into proximities, scaling the world of friends, colleagues, and family into the rectangular screens in front of our eyes. More than ever, a paradigm of navigation folds all social and economic activities into the domestic, the facial, the optical, demanding further reflection on the enmeshment of labor, exhaustion, and love into a techno-political website.” (See Editorial: “Navigation Beyond Vision, Issue Two”)

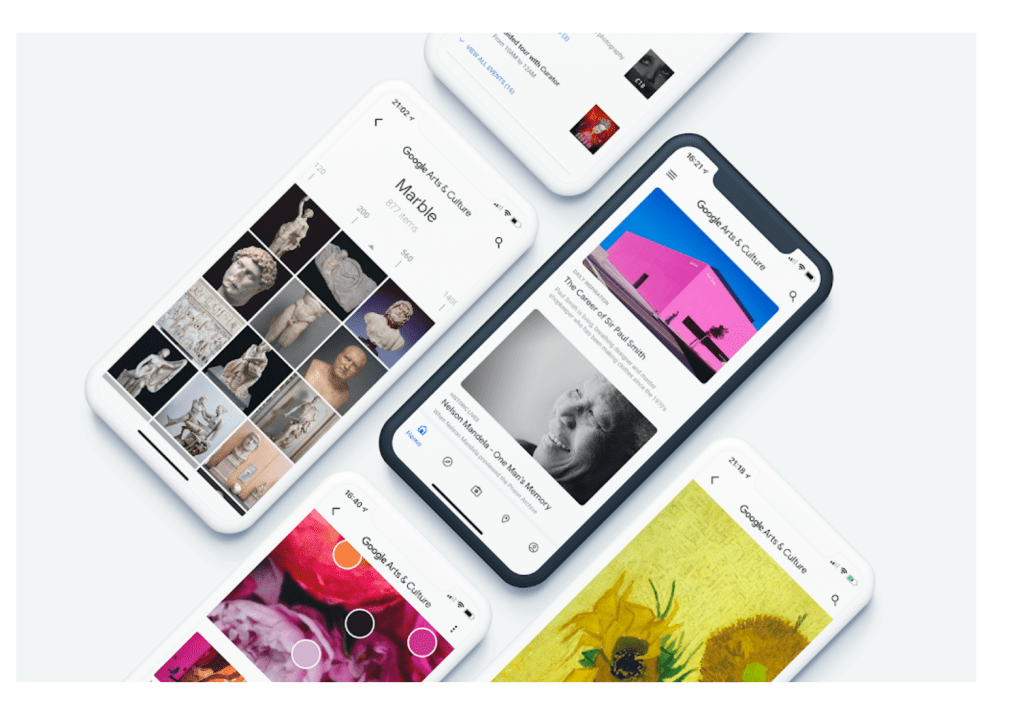

This happens at the same time that large digital media corporations and data harvesters, with enthusiastic buy-in from various state agencies, have been pushing to “digitize” public cultural institution holdings and collections. “Google Arts & Culture” announces itself “as a non-profit initiative. We work with cultural institutions and artists around the world. Together, our mission is to preserve and bring the world’s art and culture online so it’s accessible to anyone, anywhere.”

Bringing the world’s art and culture online for everyone

The “good feelings” here are plentiful.

The ascendancy within the contemporary art system of e-flux announcements, social media posting, art-blogging, website mediation of exhibition and jpeg-enabled art sales has been in place for some time. These are not COVID19-caused phenomena. However, there has been, in the context of the global pandemic, an intensification of the relays between exhibition protocols and the culture of digital networks.

In what seems like a global institutional convergence—similar in ways to the pervasive distribution of the white cube though much more accelerated—there has been a widespread adoption of the exhibition-online as the immediate solution to the demands of physical distancing, lock-down and travel restriction in the context of the global pandemic. This would seem to warrant some critical reflection and analysis in its own right. What is at stake in this drive to online exhibition? What are the operative presumptions about exhibition that inform this imperative?

The questions of exhibition (and exposition) have been activated within the debates on artistic and curatorial research. The question of how the exhibition operates as a site, agent and entanglement of enquiry has been discussed increasingly in the last decade. The spatial choreography and material assemblages of exhibition have been significant themes in this discussion. How do we think through the protocols of exhibition as enquiry in the era of the algorithmic?

the glam life of digital cultural heritage …. eu heard it here first!

GLAM is an acronym for ‘galleries, libraries, archives, and museums’ gathered under this heading to identify them all as knowledge-culture providers, givers of access to knowledge-culture more typically called ‘cultural heritage.’ (Institutions that ‘collect and maintain cultural heritage materials in the public interest’) There has been for several decades a major drive to technologize such institutions. With galleries and museums there has been an ongoing push to embed digital technologies within museum and gallery practice, especially within museum and gallery visitor experience (to ‘enhance’ and to ‘extend’ the experience).

The following extracts are from an EU resourced platform’s (2016) ‘Manifesto on Digital Cultural Heritage‘ addressed to “strategic decision makers, funding bodies, institutions, practitioners and industries in the Cultural Heritage (CH) sector, who share a common interest in the digital future and who need to act in concert.”

Just to ensure that there is no confusion, the manifesto is presented as a problematic text, not as one that is being simply cited as ‘interesting’. There is no claim here that all institutions proposing to develop and deliver content online are already subsumed within this rhetoric. The extracts are presented in place of a summary of the manifesto. This is because the rhetorical specificity of the text (the confident tone and the advocacy of the technology-value proposition) will get lost in paraphrase:

“Culture is increasingly a precondition of all kinds of economic and social value generation, a process driven by two concurrent streams of innovation: digital content production and digital connectivity.”

“Culture -and the heritage which derives from it -are economic and social assets. The ideas defined for Culture 3.0 have identified key links with innovation, welfare, sustainability, social cohesion, new entrepreneurship, softpower, local identity and the knowledge economy.“

“It is important that citizens are not restricted to being consumers of D(igital) C(ultural) H(eritage), but that they should be enabled to participate actively and to develop a sense of ownership of their cultural assets, not least within research and innovation projects and pilots involving co-creation and co-design.”

“By focusing on interaction and conceptual design, virtual multimodal museums and other C(ultural) H(eritage) I(nstitutions) will be able to offer diversified, collaborative, tailored experiences and novel exhibition design concepts that adapt to the different needs of audiences and stakeholders, including the public, students, curators and museum decision makers, researchers, technical specialists, partner organisations and other industries.”

“In line with the Culture 3.0 concept and in order to better serve its audiences and to maximise efficiency of economic and social efforts, the DCH community needs to shift towards participatory design strategies and a collaborative approach e.g. by enhancing on-site, technology-oriented museums as high-technological C(ultural) H(eritage) spaces: domes, deep spaces, immersive environments etc. with user-oriented perspectives, such as:

- providing the option to design individual tours, offering tools to better understand C(ultural) H(eritage)objects through Artificial Intelligence (AI) and/or Augmented Reality (AR), superimposing a virtual world onto the physical one or guiding users with interactive real-time maps

- interactive user experiences on the internet from anywhere in the world-sharing C(ultural) H(eritage) experiences with social community networks. This involves mapping social needs and goals and considering innovation not only as the creation of new technology but also as the novel use of existing technology.

In this respect, we believe it is important that European Commission (EC) and other programmes and projects carry out evaluations which study feedback on issues such as: audience appreciation, understandability and usability of technology applications; their impact on participation and revenues; and that they assess and verify the future expectations of audiences compared with those of professionals and curators.” See https://www.vi-mm.eu/ for more…

online ‘schools’

These questions with respect to the exhibition and the move online, resonate with debates about the transfer of educational activities – formal and informal, museum, gallery, university, high school, pre-school … educations – that have also de-camped to take up online residency. What is at stake here? Can this be approached not solely in terms of ‘gains’ and ‘losses’ – ‘compare and contrast,’ ‘before and after’ – but rather in terms of re-channelled, re-assemblages, and re-constellations of work, value, discipline, bodies and affects?

What are the ‘proximities’ and ‘distances’ – the convergences and divergences – of different online framings of exhibition and education with respect to other online ‘presence’ regimes, say, 4chan or 8chan, or say a certain presidential tweet machine, or say a WhatsApp lynch mob, or say the facebook ‘feed’ of a murder?

This might be taken in one sense as a question about the relationship between sociotechnical form – online digitally networked synchronous and asynchronous ‘community’ – and sociocultural content – the explicit foreground purposes, formats, themes, tones and relational dimensions of ‘communication’? It is a question against the presumption that different sociocultural content constitutes the substantial differentiation between all the above online ‘presence’ regimes.

It is also a question about the relationship between an institutional ‘core’ and the digital network ‘extension’ of that institution. It opens the possibility that institutions that understand themselves to have attached a new annex – ‘our online gallery’, ‘our social media presence’ – may come to experience themselves as having been annexed to another institution altogether. Without proposing any simple technological determinism, it may be that public sphere analyses (elaborated in response to print and cinema cultures, and telecommunications-based mass-media cultures of radio and television) are not adequate to the task of thinking the public institution in the algorithmic domains of dataculture.

If you are interested to explore more material in respect of these questions of online culture, surveillance capitalism and the digital abstraction of life transformed into data, here are some sources that might be of interest. For a museum perspective with respect to ‘exhibition online’ see Kajsa Hartig’s (Head of Collections and Cultural Environments at Västernorrlands museum) account of the issue as rehearsed in twitter discussions in (2019) “Museums in the digital space—some reflections on online exhibitions.” This source is cited by way of an example of the wider professional field’s responsiveness to the digital culture access agenda.

For a more theoretically intense, and primarily critical, discussion of data gathering, algorithmic governance and education see Ramon Amaro’s (2020) essay on the collecting of large quantities of data to model human behaviour in UK higher education “Threshold Value.”

The Transnational Institute’s recent webinar on ‘Taking on the Tech Titans: Reclaiming our data commons‘ is another interesting place to start, particularly in terms of the macro-analysis of corporate tech initiatives to condition the terrain of digital data economies and ‘legally’ disable state regulation through WTO and similar multilateral spaces of corporate policy shaping and influence. This is useful for understanding how the discursive frames of the policy advocacy of technology-value and dataculture are being conditioned in global – and not just EU terms.

Following on from this workshop, there was a panel discussion in the EARN (2021) conference “The Postresearch Condition” entitled “Expo-facto: Into the Algorithm of Exhibition.” There is a short report on that panel here.